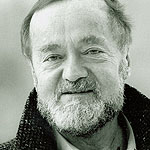

Stephen Toulmin RIP

Stephen Toulmin, without question a founding father of modern argumentation theory, and in particular, the inspiration for hypertextual, semiformal representation of argument structures, died on Dec 4th.

Stephen Toulmin, without question a founding father of modern argumentation theory, and in particular, the inspiration for hypertextual, semiformal representation of argument structures, died on Dec 4th.

I first encountered his seminal work The Uses of Argument during my Ergonomics Masters at UCL in 1988, in preparation for my PhD in cognitive aspects of hypertext: argumentation was the experimental white rat of hypertext representation research in the 1980s/90s. The pragmatic, ethical stance of his work has been an inspiration for my own efforts to apply argument mapping and structured deliberation technology to tackling wicked problems.

A telling extract from the USC obituary:

As director of the College’s School of International Relations, Steven Lamy recalled Toulmin working with students on projects related to the role of global civil society in creating a just and peaceful world.

“He made a real difference in the lives of his students, encouraging them to be scholars who cared about the world,” said Lamy, professor of international relations and the College’s vice dean for academic programs. “He didn’t just write about moral reasoning and ethics, he lived a moral and ethical life. He cared about his students.”

Toulmin’s most influential work was the Toulmin Model of Argumentation. In it, he identified six elements of a persuasive argument: claim, grounds, warrant, backing, qualifier and rebuttal.

In his seminal book The Uses of Argument (Cambridge University Press, 1958), he outlined the argument model. The book investigates the flaws of traditional logic, maintaining that some aspects of arguments can vary from field to field, while other aspects are consistent throughout all fields.

Arguing against the absolute truth advocated in Plato’s idealized formal logic, Toulmin said that truth can be relative. Historical and cultural contexts, he said, must be taken into consideration.

He concluded that absolutism fails to consider the field-dependent aspects of argument. Advocating a universal truth, absolutists believe that a standard set of moral principles — regardless of context — can solve all moral dilemmas. But Toulmin purported that many of these standard principles cannot be applied to day-to-day life in the real world.

After pinpointing absolutism’s dearth of practical value, Toulmin developed a new type of argument, called practical arguments. He urged philosophers to apply their abstract theories to practical debates over real-world matters such as medical ethics and environmental policies.

“It is time for philosophers to come out of their self-imposed isolation and reenter the collective world of practical life and shared human problems,” he wrote.

One problem with the utility of argumentation in general is that many references are copyrighted and cannot be presented in direct form in a consolidated view. On the other hand, ideas are not copyrighted, so if the presented form is very different from the original one, copyright does not inhibit their incorporation.

Thus, anyone with access to a reference document can construct, for example, a Compendium map which claims to represent the relevant ideas of that reference and include it along with other material. This can result in much quicker access to the wide range of ideas which typically apply to every important question.