The Writing Synth Hypothesis

The Writing Synth Hypothesis

Reflecting on where writing is heading seems critical as, within education, we think about the future we should equip our graduates for, which in turn should shape the future of writing pedagogy and assessment.

The hypothesis

Synthesisers transformed music composition fundamentally. As personal computers became widespread, and digital audio workstations with built-in instruments and effects became affordable in the late 1980s, the masses could start tinkering with audio tracks without needing to learn an instrument or the formal fundamentals of music. Non-linear editing was a fundamentally different way of composing, enabling the flexible exploration of creative options.

The Writing Synth hypothesis proposes that with the emergence of generative AI, authors will be able to learn writing in new ways, democratising writing just as we saw with music synthesisers.

Now we need to learn to play these new instruments.

There may be new genres of writing that, like the music revolution, were impossible to create without these new tools.

This is a working hypothesis.

- It needs to be tested conceptually (does the argument by analogy hold up?).

- There’s important user interface design work to do (since writing is different to music, how will we orchestrate texts?).

- And the vacuum of evidence must be filled (what does such writing look like in practice, who is capable of it, and does it assist learners of all ages and stages?).

Let’s take a walk to explore this new space.

Music synths: data, interoperability, UX

The music synth revolution was possible thanks to a radical new data and interoperability infrastructure. Analogue and then digital synthesisers could be connected to computers thanks to the new underlying standard for digitising and transmitting audio signals between devices called MIDI (Musical Instrument Digital Interface). But a data infrastructure is only useful when humans can interact with it, which brings us to the user experience (UX).

Younger readers will not recall a time before visual text editors. The ability to translate thoughts onto the screen fast enough to keep pace with one’s thinking was a revolution, first demonstrated in 1968 by Doug Engelbart in his extraordinary Mother of all Demos. We can barely conceive how revolutionary it was in the era of the typewriter and tickertape, to see someone type something, change their mind, and instantly edit it. With the PC revolution led by Xerox, Apple and Microsoft, we moved from command line interfaces (where the user had to type arcane command syntax and semantics) to what were first termed WIMP (Windows/Icons/Menus/Pointer) Graphical User Interfaces (GUIs), which we of course now take for granted. These displays were revolutionary, constantly reminding the user what commands were available via icons and menus (exploiting human recognition instead of recall), offered complementary, interlinked views of data (in these wonderful new windows) which could be arranged on screen, with myriad interactive ‘widgets’ such as checkboxes and sliders to set preferences.

The arrival of non-linear editors orchestrated these fundamentally new ways of interacting with digital assets to transition musical composition into playful experimentation with interactive, visual, multitrack timelines. Now, like text, audio edits had “undo”, and clips could be dragged+dropped, copied+pasted, merged+split, and ‘formatted’ by tweaking their many audio properties. Video followed closely behind, once computing hardware caught up to handle storage and resolution challenges.

Envisioning the AI Writing Studio

As someone coming from the Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) community, I am drawn to design prototypes as one way of envisioning the future, so we’ll kick off with that. The chat interface in OpenAI’s ChatGPT has seized the world’s imagination with its simplicity, providing the first walk-up-and-use interface to the large language model capability (which had been available for several years via GPT APIs, but only to technical experts). Everyone knew what textchat was, and it reinforced the conversational metaphor that played to the public’s sci-fi imaginations. The addition of voice input and output consolidated that narrative — at last AI had delivered HAL, C-3PO, DATA and all our other favourites from the movies. Our baby AI can talk (apparently about anything, with great confidence) and we’re absolutely besotted!

But when we remind ouselves that the user interface is a way to control a powerful computer, a chat metaphor is not the only, or even optimal, way to perform all tasks. In one sense, it’s a variant on the good old command line interface that preceded GUIs, requiring the user to know, like a magician conjuring spells, the commands that will invoke the most powerful effects. Those who have reached moderate to expert levels of proficiency with the Unix command line revel in the power this brings to control in ways that are impossible one click at a time in a GUI. We see the rise of this new art as people delight in figuring out ways to make ChatGPT do their bidding, and set themselves up as Prompt Engineering gurus. This is fun while we all play — but if you need to do serious work, the idea that you need to approach your AI assistant with guile and cunning — as though they’re a tetchy colleague you have to manipulate to get them to cooperate — seems odd to say the least.

While learning to control the output of language models is certainly a form of AI literacy, the need for “prompt engineering” may be consigned in the history books to a curiosity associated with the earliest releases, as people sought to use the chatbot not just for conversation, but as a practical creative tool. A command line interface with highly unpredictable output is not the optimal user interface for co-creation.

How might the UX evolve ? Firstly, taking inspiration from the music revolution, I anticipate the emergence of writing environments will enable authors to orchestrate their writing in new ways. Perhaps the introductory user guide to an AI Writing Studio (Sept. 2023 Release) will describe functionality like this…

- Source Apps. Select which AI writing generators you want to work with — the studio will render their drafts in different windows which you can arrange, refreshing them each time settings are changed. After a while you may figure out which ones work best with different styles, which ones are most responsive, or which ones are most fun!

- Genre menu. Choose the genre of writing you want to work in (e.g., tech blog; journal article; business report; etc.)

- Modulators. Configure the libraries of sliders down the side that you want — these remind you how the text can be modified and encourage experimentation, applied either to the whole document, or the selected text (e.g., length; formality; reader age; etc.)

- Record On/Off. Turn on recording to log your studio session, enabling Replay and Analytics (see below).

- Replay. Fast Forward/Rewind through your document’s timeline to revisit key moments (e.g., recovering the state of the modulators and each app’s draft at a given moment — you can branch your document and explore another version).

- Analytics. AI is used to generate summaries of your usage of AI generators, such as how much you request, reject, adopt or adapt AI suggestions. This helps evidence your critical engagement with AI, which your course will have mentioned. Check if your assignment requires you to include the WAL (Writing Analytics Link) and/or the 1-page report.

- Feedback Tips. The feedback panel uses the best research on writing to assist your writing skills. In addition to the Analytics, other tabs show you well established indicators of the clarity of writing, and the depth of your reflection and argumentation (varies with the genre you chose). The analytics are your springboard into our personally recommended Practice Exercises and Pro Tips…

- Practice Exercises. These help you get the most out AI writers, while ensuring that you’re building your own writing and thinking skills.

- Pro Tips. We curated some of the best videos from our elite writers, who walk through their writing practices with Writing Visual Studio.

At some point perhaps I’ll mock the interface up, and even get to build it. But these are just preliminary ideas — there are far more creative possibilities, introduced next.

Moving beyond AI as ghostwriter demands creative UX design

Glenn Kleiman helpfully discusses (with the aid of GPT) the roles that AI writers can play — as editor, co-author, ghostwriter, and muse. The panic around cheating focuses on AI as ghostwriter, and we will watch the inevitable arms race between AI generators and detectors play out. Policing is important, but not the only mindset we need to adopt. What might interaction with AI writers playing the other roles look like?

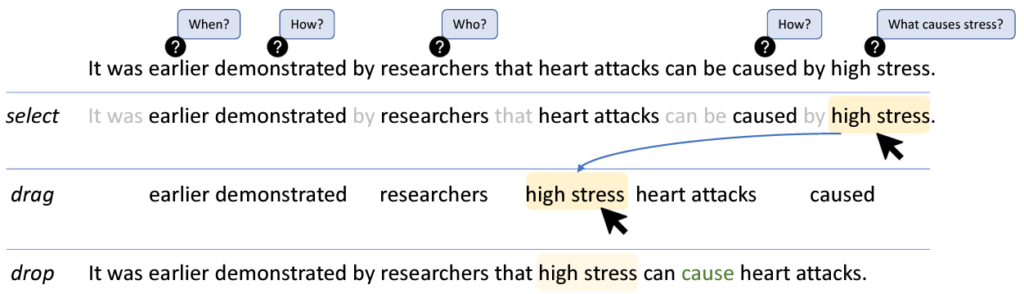

We find clues in the communities spanning both academia and the tech industry who’ve been working on Computational Creativity and most recently, Human-AI Co-Creation with Generative Models. Consider Ken Arnold and colleagues, prototyping generative AI that augments rather than automates human writers. The purpose of the AI is to prompt the author with questions, promoting more critical thinking and better writing:

A team at MIT and Harvard are exploring the addition of audio and visual cues for creative writers, along with text: this paper exemplifies the kind of detailed analysis of tool usage that the Writing Synth hypothesis requires:

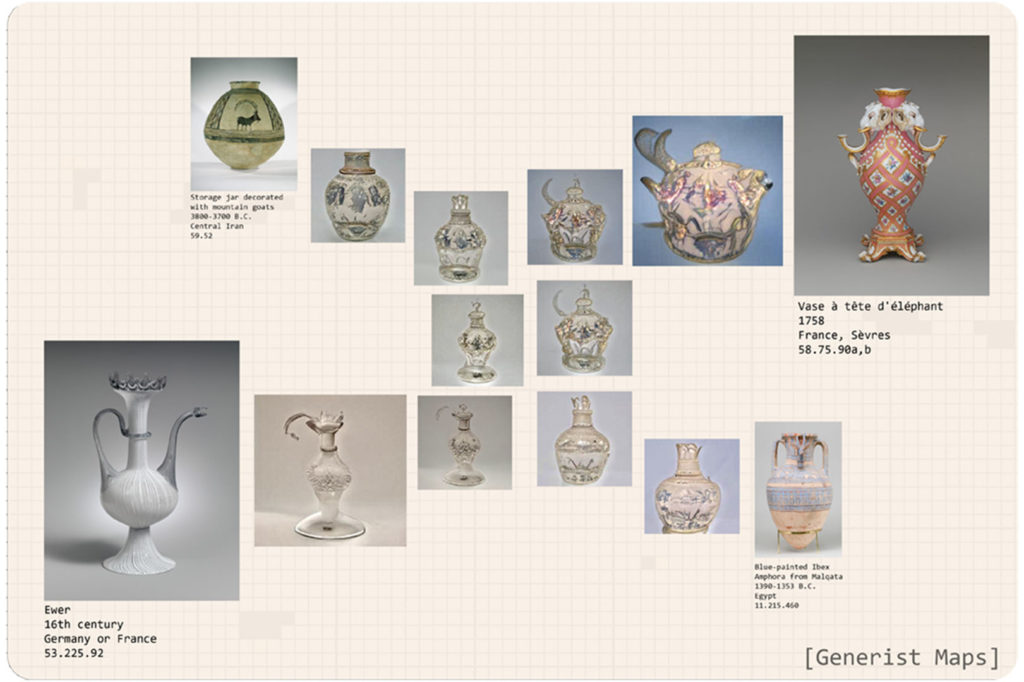

Continuing with creativity, consider the extraordinary work of Sarah Schwettmann who shows in this keynote talk how generative AI for The Met renders images of cultural artifacts that fill the gaps between artifacts that have been discovered. Thus, using “Generist Maps“, we can ask what might have happened if two cultures had met?

If this is possible for images, then is it not plausible to envision AI writers drafting texts in the interstitial spaces between known evidence, or between polarised positions in an argument? And might visual interfaces such as the above not be an engaging way to work with drafts ?

In another project, Schwettmann’s team describe the Latent Compass, a prototype to help individuals generate images that match their intuitions about the meaning of complex terms (e.g., “more festive”, “more inviting”). In a writing context, I can see authors teaching their AI assistant with examples of what they mean by “the crisis motivating a research program”, or “artful critique of an argument”, which become new, user-defined modulators. I would see such developments as evidence for the writing synths hypothesis.

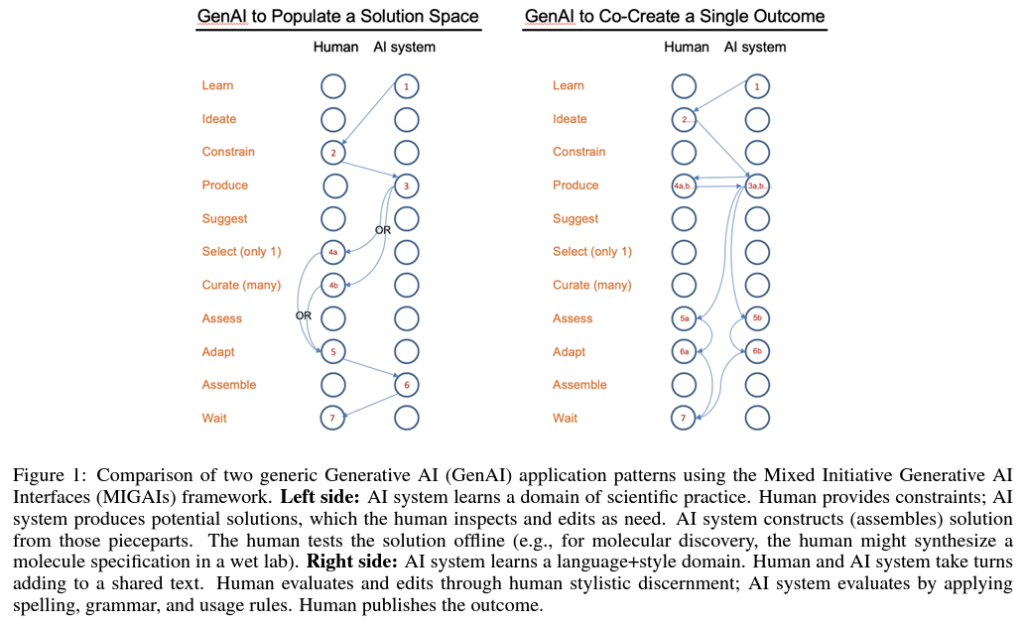

The Human-AI co-creation community also offers us conceptual language to describe how the human and AI can be configured to co-create together, such as this example from Michael Muller and colleagues:

[Update 27 Mar 2023] Most recently they have proposed a set of user-centred design principles to guide generative AI tools, which I am looking forward to thinking through in relation to the writing studio concept:

So, those are glimpses of where we may be heading with human-AI co-writing. But right now, in the true Silicon Valley ethos of “move fast and break stuff”, we are witnessing the largest scale introduction of AI in education, with no evidence of its utility for learning. And it is in the trenches of everyday education, at school and university, and professional learning in the workplace, where the writing synth hypothesis must be tested.

Teaching and assessing writing: many hopes and fears, little evidence

GenAI is a system shock because teaching and assessment regimes rest on the assumption is that the learner has written the text, and that the goal is to assess their ability to do so unaided by anyone or anything else (other than the passive capabilities of word processors). Learners may, of course, draw on others’ work, but only following well-established guidelines (e.g., through quoting and citing), in order to maintain academic integrity. Some students cross the line into the territory of student misconduct (the reasons for which are complex), and an array of policies and software products to police this are in place.

However, rather than simply banning AI writing, this has also triggered an outbreak of creativity as educators share and debate ways to actively embrace the new possibilities of composing with AI, as a new way to cultivate students’ critical faculties. This is in my view absolutely the way forward. Our graduates must know how to orchestrate these instruments and (to borrow an aviation metaphor) fly them within their ‘flight envelope’ — understanding the limits within which they can be trusted to perform reliably, before the wings drop off… Beyond that, if they’re to find work in the creative professions, students must be able to show the additional value that distinguishes them from 100% AI-generated writing, or mere AI app operators who can simply click buttons.

In my own university we are advising effective ethical engagement, and resourcing academics for shorter and longer term adaptation of their assignments, and most other universities are doing the same. This is a holding pattern while we wait for the dust to settle. The web is full of proposals for engaging students in using ChatGPT creatively (101 ideas), while others warn of the death of thinking. These myriad hopes, fears and advice are filling the vacuum of evidence at this transition point. In a year’s time we’ll have many anecdotes and practitioner reports, and the first robust peer reviewed research evidence.

However, while generative AI is undeniably new, we are not in completely uncharted waters. AIED research has been under way for over 40 years. There are communities dedicated to prototyping and evaluating computational support for writing, conversational user interfaces and pedagogical agents, to name just three at the intersection of ChatGPT as a design concept. The media conversation would be more informed if these researchers can translate their work into accessible forms for wider audiences, as well as apply their expertise to show how generative AI can be designed and deployed in ways that respect with what we already know. We’ve made a start on that conversation in my own institution.

[Update 14 Aug 2023: An expert forum on the future of assessment in the age of AI just wrapped up, and the report will be shared in this TEQSA webinar]

Knowledge, skills and dispositions for critical engagement with AI

Amidst all the excitement among the optimists, let’s consider one of the most prevalent aspirations: that students will critically engage with AI draft writing, identify its weaknesses, and show how they have improved on it in their submitted work. While academics proposing these ideas are able to do this, I wonder if they overestimate their students’ knowledge, skills and dispositions to do so.

- Curriculum/domain knowledge is needed to validate factual claims and spot significant omissions.

- Rhetorical analysis and writing skills are needed to improve on prose which may in fact exceed many students own ability

- Dispositions such as the curiosity and authenticity are needed to resist the temptation to just run with what the AI served up.

These qualities must be demonstrated rather than assumed, and educators should design for wide variability among their students in their capacity to critically engage. This is just one example of the evidence that needs to be gathered. [Update 8 June 2023: after 1 semester teaching with ChatGPT, we have initial evidence]

[Update 27 Mar 2023] The Academic Integrity debate around generative AI is (understandably) skewed to the ‘dark side’, and badly in need of more sophisticated vocabulary to talk about what it means to write with integrity with AI. Katy Gero’s exciting research illuminates how creative writers feel about AI writing aids, and is exactly the kind of work we need now. I’ll highlight just one aspect of her work, around the differing ways that writers feel about “authenticity”:

“Writers talked about authenticity, or their ‘voice’, as a concern when it came to incorporating the ideas or suggestions of others. Here, we describe four types of authenticity issues that came up in our interviews: 1) the reader’s sense of authenticity, 2) the impact of viewing suggestions, 3) differing opinions on where authenticity lies, and 4) human v. computer authenticity issues.” (Gero, 2022: p.106)

Gero’s work may offer us concepts and language to help students develop their own sense of what it feels like to work authentically with AI writers.

Writing analytics and academic integrity

(An earlier version of this section was originally posted here)

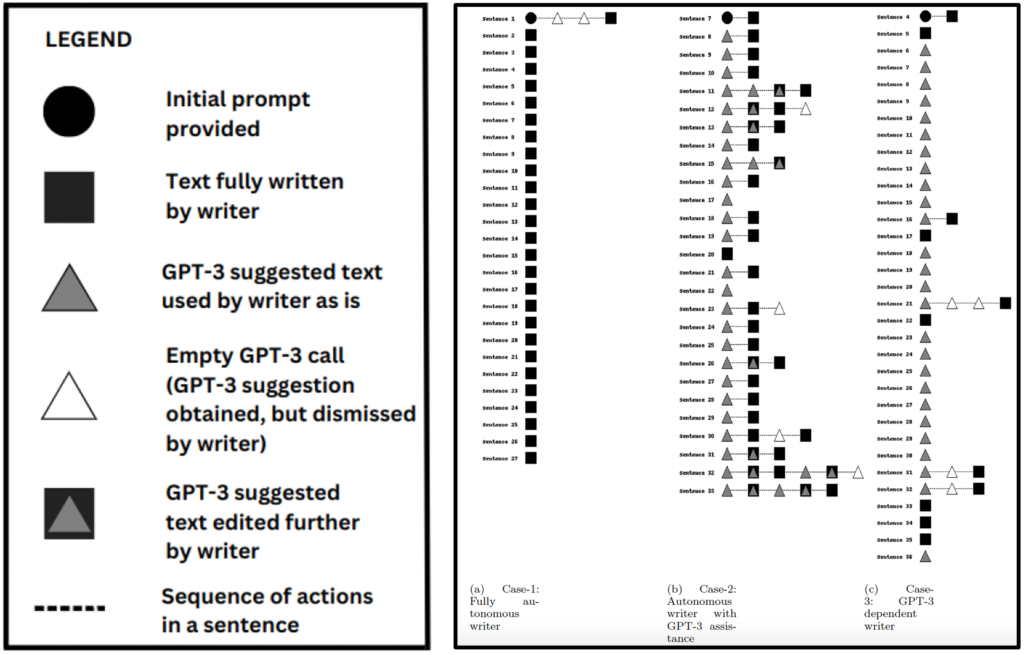

Recall Analytics in my envisioned writing studio. In the near future, GenAI will be fully integrated into interactive tools for writing, coding, and other creative work with image, music, animation, video etc… I envisage our students will become power-users. Human-AI interaction ‘flow states’ will become a synergistic blur, as prompts are invoked by the learner or offered by the machine, and rejected, adopted, adapted — each in the space of a few seconds. Tens of thousands of times in the production of an assignment.

Asking a student to “declare/document what role AI played” after hours/days/weeks of working in close partnership with such tools now becomes an impossible question to answer.

Instead, following the Writing Synth hypothesis, we look to the music world and borrow a studio recording session analogy: we immerse ourselves in our work, it’s all being recorded, and then we need to replay and review, dissect and debate, re-record elements, or start over…

In educational terms, such tools will be scaffolding “reflection-on-action” (Donald Schön) by the learner, possibly also with peers, and the teaching/coaching team. In time, they develop the capacity to engage in increasingly nuanced “reflection-in-action”, making improvised decisions about how and when to call on AI… In the language of human-computer interaction research, such tools will support Retrospective Cued Recall.

Analytics crunching that data will make visible patterns that are useful for improving performance. My colleague Antonette Shibani has already prototyped this (see below). We will be able to see — literally — how virtuoso performance with such tools differs from less developed performances. This can serve as formative feedback to the learner, and assist should academic integrity questions arise.

[Update 26 Apr 2023] Antonette Shibani, et al (2023). Visual representation of co-authorship with GPT-3: Studying human-machine interaction for effective writing. 16th International Conference on Educational Data Mining

The fundamental question, then, is whether students are learning to produce great work. And in the future, great work will not be merely what can be automated. As Michael Feldstein has noted, students must learn the limits of GenAI, so that they develop the qualities needed to produce work that is beyond full automation — and stay employed.

And so we return to assessment.

If you can’t write without AI, can you really write?

In a prescient paper written at the turn of the 90s, Gavriel Salomon, David Perkins and Tamar Globerson considered critical educational questions that they envisaged arising with “intelligent technologies” as they termed them. When we ask what effect AI has on students, they distinguish between performance with the AI, and the effects of using AI on the student, assessable once the AI is removed. Intriguingly, they invite us to imagine a positive, futuristic scenario:

“For another illustration, consider the possible impact of a truly intelligent word processor: On the one hand, students might write better while writing with it; on the other hand, writing with such an intelligent word processor might teach students principles about the craft of writing that they could apply widely when writing with only a simple word processor; this suggests effects of it.”

Well, here we are! Fast-forward 30 years to today, and some have argued that ChatGPT is an educational disaster because we only learn to think by writing (Rob Reich, p.20). Decades of research into writing does indeed show that the writing process activates many cognitive faculties for critical thinking. But the roles that a conversational, generative AI agent can play in provoking deeper thinking (see above examples) are not taken into account by such cognitive models, which assume a solo author.

Salomon et al. argue for mindful versus mindless engagement with AI to achieve high performance with AI, and pose the assessment question now confronting us today: should we evaluate what a student is capable of when using AI to augment their intellect, or the “cognitive residue” as they term it — how well they perform once stripped of the AI ? For many educators, it would be a dereliction of duty to turn out graduates who could not write well with a pen and paper, while for others, that is to be stuck in the past. The imperative is to graduate capable of high performance with a profession’s state of the art tools. It may of course be a false dichotomy if the latter is impossible without the former, but that is an empirical question.

Writing in the early 90s, pre-Web, pre-mobile, pre-Big Data, and pre-LLMs, the authors conclude that we cannot afford to assess only AI-augmented student performance. After all:

“Until intelligent technologies become as ubiquitous as pencil and paper—and we are not there yet by a long shot—how a person functions away from intelligent technologies must be considered. Moreover, even if computer technology became as ubiquitous as the pencil, students would still face an infinite number of problems to solve, new kinds of knowledge to mentally construct, and decisions to make, for which no intelligent technology would be available or accessible.”

We might question this assumption now — but something deep inside us as educators might whisper that we will have really lost the plot if our graduates cannot function without computational support. The resolution may lie in what exactly we want students to bring. Rose Luckin and Margaret Bearman have argued that it is pointless to assess students on anything that AI can do better, which is a rapidly rising waterline (Salomon et al. contest this). I’ve also argued that we need to move to higher ground and harness analytics and AI to help where they can in cultivating the qualities and capabilities that are still distinctively human. How about we start with dignity, compassion and justice.

To close…

So, that’s the Writing Synth Hypothesis. I had fun writing it — let’s see how it all unfolds. This is indeed an extraordinary time.

Your comments are most welcome: my blog doesn’t have great discussion tools, so join the conversation in this LinkedIn thread.

- March 2024 update: A design space for AI writing tools (CHI’24)